⁄A Genuine Moment

Oil on canvas, black & white.

Charlie Bierk paints in a studio on Niagara Street, somewhere between Queen and King that he shares with two of his brothers. The studio directly beside him is occupied by another brother Alex, who also paints.

Buster, the Boston Terrier, sits staring intently at the treat hovering above his nose. Moments earlier he was scampering around the studio, darting among working materials, photography lights and Charlie’s massive black and white photorealistic paintings. But now the mood is tense: a moment of unbearable suspense for its own sake. Buster drops all pretenses of politeness and drools all over the floor. The treat might as well be resting on his face. From a large canvas leaning against the wall, Charlie’s girlfriend Martha looks on fixed in black and white, her hair a mess, wearing a serene expression.

In a few seconds, Buster has proved his worth as studio dog, and is being whisked out the room. From the doorframe, Alex turns around with a laugh and says, “Be careful what you say.”

Charlie comes from a family of talent. In addition to his brothers working close by, he is also sibling of musician Sebastian Bach and ex-NHL player Zac Bierk. Their father is the late David Bierk, a renowned and influential contemporary artist. Having been taught early on the same technique by their father, Charlie and his brothers share a similar process, though their subject matter and style’s diverge considerably.

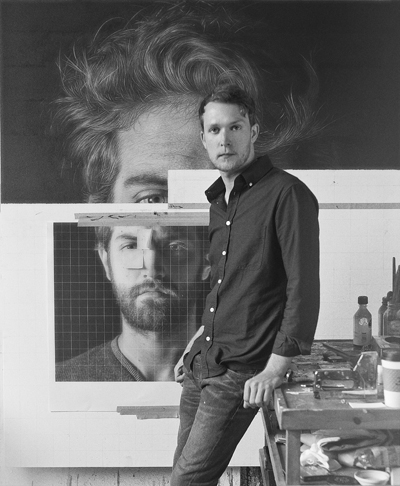

“I use a grid technique, which is quite an old way of painting,” Charlie says. “I take a photo first, usually of a friend. I’ll take a ton of photos, but one always stands out. It’s really tough to say what that is, but for the most part I think it’s a gaze.”

He gets his image printed, enlarged and turns it into a grid on his canvas. “From there, I work square by square, the way you’d read a book, from left to right, top to bottom.” His paintings, which take about a month and a half to complete, are huge: close to six by four feet. The effect of the precision and size is striking: every pore, every strand of hair has been transferred to the larger than life canvases.

Charlie is currently working on the large portraits that will be featured in his show Frames Per Second at the Nicholas Metivier Gallery from July 18 to August 19, 2012. It is his first major commercial show since he graduated from OCAD last year. The show will include four large works, along with smaller, more experimental pieces.

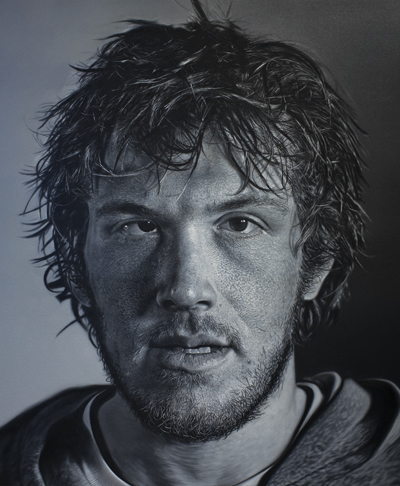

One piece that will be in Frames Per Second is a portrait of Bierk’s friend Ben. It is particularly remarkable both because of Ben’s ambiguous expression and his crossed eye. “When I finished that painting, I knew there was something special about it,” he says. “And I think it came down to the expression he gave me. I don’t think it was technically anything different than the rest, but it was just capturing that precise moment that made the painting what it is. I took about a hundred photographs of him. The rest are kind of goofy and weird but that one spoke to me.”

Charlie had already, as a child, realized that he wanted to paint for a living. He has been perfecting his technique ever since. The Bierk siblings started visiting their father’s studio three to five days a week after school when each was around nine years old.

“He taught me and my brothers all the same way to paint, which was using this grid technique,” he remembers.

Their father gave them each the goal to paint twenty black and white portraits first. It was important that they nail black and white before moving to colour work. “That went on for a while,” he says, “and I kind of got stuck in black and white. I never moved on from that.”

“I think that comes from a whole world of things, both technical and personal,” he says, when I ask him why he often paints friends and family. “A lot of it has to do with loss: dealing with loss and, you know, grasping onto the people who are in my life and aggrandizing them; showing their role in my life as people special to me.”

It is also about capturing the features that make people unique: Martha’s wild hair and nose ring, or Ben’s crossed eye. “I try and make my works as honest as possible. I’m looking for a moment of pure emptiness, but also pure honesty: A genuine moment.”

Charlie remembers the moment he knew art would be his life. “When I was a kid my dad took me to a Chuck Close retrospective in New York. As I walked in, I thought his works were photographs. I got a foot away and still thought they were photographs until my dad told me that they were paintings. Since then I always wanted to be able to do that to people: to have them get inches away from my paintings – even touch them – to see that they are paintings.”

Though Charlie will spend weeks working delicately on a moment frozen in time, it all comes down to an instant: that first feeling of awe and inspiration, passed on to someone stepping into the gallery.